The Truth

Below is a newspaper article from 1982 about Bob Kieser Sr – Greg Kieser’s late father – and, at the bottom, are a couple of family pictures. In an interview with Man in the Mirror, Kieser related the truth covered in this article to the fiction in the novel; “I wrote fiction because I wanted to convey the truth of my story not necessarily just to present a list of things that happened to me…”

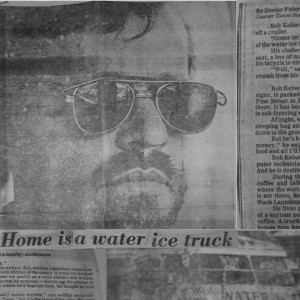

HOME IS A WATER ICE TRUCK

by Denise Foley, Bucks County Courier Times Staff Writer

Bob Keiser answers his door warily, slowly chewing the top off a cruller.

“Come on in,” he says finally, yanking back the metal door of the water ice truck that is his home.

His clothes are packed in a leather suitcase by the driver’s seat, a box of macaroni is perched on top of a rusty propane stove, his bicycle is virtually folded into a corner, under a foam mattress.

“Well,” says Keiser, leaning on his crutch, brushing a donut crumb from his beard, “this is it, this is where I live.”

***

Bob Keiser’s home, a Chevrolet truck plastered with for-sale signs, is parked behind a chain link fence at the Exxon Station on Pine Street in Langhorne. He is not clear how long he has been there. It has been long enough for him to learn how to keep warm in sub-freezing weather.

At night, when the temperature dips, he rolls himself into his sleeping bag and curls up “like a groundhog,” he says, “I just go down into the ground and let my body and fur keep me warm.”

But he’s kept his sense of humor about it. “If I ever get some money,” he says, his blue eyes glinting, “I can buy some frozen food and all I have to do is pile it up.”

Bob Keiser, 42, is a widower with six children, a former computer technician and ex-mental patient. He says he has cancer. And he is destitute.

During the day, he sits for hours across the street sipping coffee and talking to patrons at the Crossroads Luncheonette, where the waitresses tell him he looks like Peter Fonda. When he is not there, he is reading discarded newspapers at the Shop ‘N’ Wash Laundromat.

He lives primarily on handouts. Bob Keiser is the recipient of a curious public charity. Patrons at the luncheonette buy him coffee. A truck driver who does his laundry at the Shop ‘N’ Wash brings him bread and lunchmeat. The waitresses at the Crossroads keep tabs on him. “I wish,” said one guy, “somebody would do something for him. He’s a really likeable guy.”

***Read Reviews of American Spaz The Novel***

Some people try. People like Earl Wismer, the 71 year-old retired mechanic who was known as Langhorne’s “pretzel man” when he sold pretzels and water ice. It’s his water ice truck Bob Keiser lives in. Keiser and his family were his neighbors a few years ago, when Bob Keiser was another person.

“He was a perfectly normal, industrious sort of guy,” recalls Wismer, an amiable, talkative man who’s now “mostly homebound.”

“Yeah,” he says, “he used to drink with my oldest boy at Marty’s Bar. My boy was killed about 10 years ago. Yeah, I used to marvel at the two of them when they got their heads together. They got along real well. His kids used to come and buy bubble gum off me when I had my truck. His wife was a very lovely creature. Put you in mind of the girl that used to be on the Tag commercial. Loretta Young. This really is heartbreaking for me. This man was my neighbor.

Wismer offered the use of the water ice truck after Keiser turned down his offer of a room at Wismer’s Langhorne Terrace home. Wismer had found his old neighbor sleeping on table in a park.

“I got seven rooms and it’s just me and my wife,” says Wismer. “I told him, ‘Bob, you can’t be sleeping out in the cold.” But he couldn’t get head nor tail of anything I said to him. He seems to talk garble to me. He says nothin’. I feel so sorry for him. I know some politicians and I could pull some strings. But it seems he wants to be fancy free. The whole thing is a mystery to me.”

***Watch the short film “How I Became a Spaz (and you can too)”***

Keiser himself provides few clues. Though he is well educated—he studied for a time at Drexel University—he often rambles unintelligibly. He reveals his life frugally, one small fact at a time.

But his problems seem to stem from a snowy night in December 1978, five days before Christmas, when his Volkswagen spun out of control on an icy road in Mt. Holly and hit a tree. His wife, Mary Louise, was killed, and Keiser was critically injured. He remembers nothing about the accident.

He says he suffered a fracture skull, a broken hip and two broken shoulders. He still walks with a limp, maneuvering across icy Pine Street with a battered wooden crutch.

After a month in the hospital, says Keiser, who pokes a cigarette between his thick gnarled fingers, he went home—to a remodeled Country Clubber in Red Rose Gate—for an extended leave from his job at a Norristown computer firm. He was eventually fired, he says, “because they said I was insane.”

He says he spent some time in Doylestown Hospital for emotional problems, and a few months in group therapy.

His six children, who range in age from 10 to 22, are either on their own or with his wife’s relatives. He says he sees them periodically. “They treat me well. I had a nice Christmas dinner with them.” But he won’t accept any help from them. “I’m their father and that sort of thing,” he sayd. “I’d rather, if anything, be giving them too much help and have them push me away.”

He has been on welfare. But, welfare regulations require recipients to have a valid address and welfare officials wouldn’t accept his proposal—the he use the address of a self-storage firm where he’d kept his tools. He thought he could also live there.

“I know it really sounds terrible,” says welfare social service worker Paula Trout, “but it’s the tenor of the time. We can’t have people passing through, collecting welfare all across the country.”

But she was sympathetic to Keiser’s plight. She’s seen cases like his before, and they leave even the most compassionate social worker helpless.

“He’s one of those people who falls through the cracks,” she says. “Everything that’s set up in our system, everything that’s set up for psychiatric care, he falls through. Within the law, he has to be willing. If he’s not a danger to himself or others, he can’t be locked up. He does have a right to be out there. He still has freedom of choice, which is good. I guess.

***Buy American Spaz The Novel***

Bob Keiser says he’s not unhappy where he is. He wears layers of cast-ff clothes to keep warm, spends his days in amiable conversations and when the temperature drops too low he spends the night “sitting up in an all night restaurant.”

“It’s all tolerable,” he says with a shrug.

But he is aware that he is not eating well. “Some people bail me out with food, but there are certain basics of health food I’m not getting—meat and potatoes,” he says.

And he would like to have “a room or an apartment somewhere where I can do my writing.” He talks vaguely of starting legal proceedings against his former employers, the car company, the government. “I need a devoted public defender devoted to my case only,” he says. “I’d like to get my hip fixed.”

But Bob Keiser is less concerned about himself than are the people who have come to care about him.

People like Earl Wismer.

“You know, I was out on the cold once,” says Wismer, “One time in Texas, a long time ago. I can tell you how it is living in the cold. I was riding the rails then. When I was in Illinois, I offered to work for a farmer just to have a place to sleep.”

“I don’t care who it is, nobody deserves that. And there’s no reason it should happen to a guy like him. They were a happily married couple, they had nice children. I’ll tell you, it just breaks my heart.”

|

|